November 23, 2022

Coping by Camouflage

By Dr Kathy Weston

Reflect

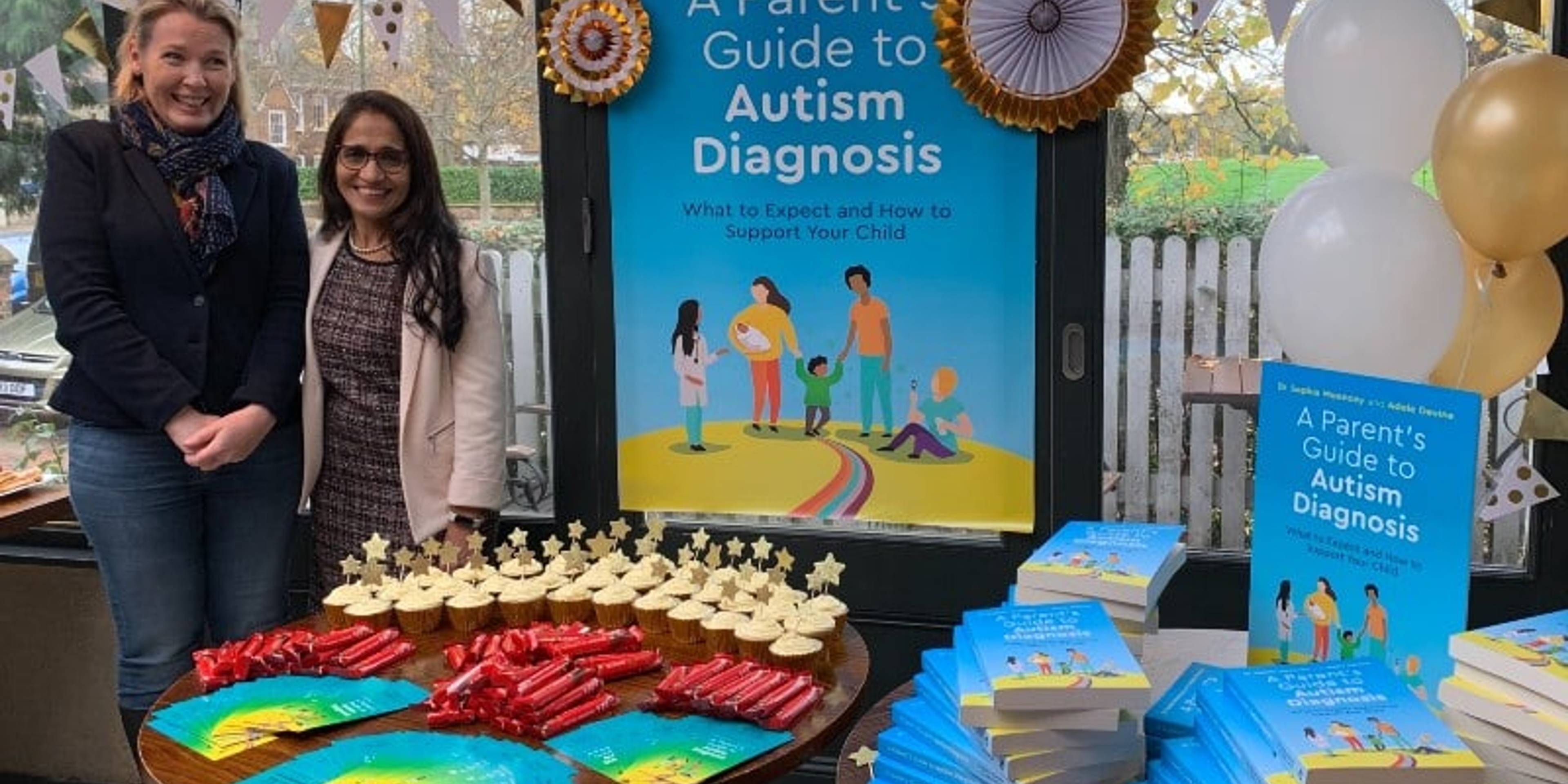

Last weekend, I had the pleasure of attending a book launch, hosted by leading Consultant Paediatrician, Dr Sophia Mooncey, who is an expert on neurodiversity and author of the recently published: A Parent’s Guide to Autism Diagnosis: what to expect and how to support your child.

It isn’t unusual for a family to receive a diagnosis of autism for their child and to feel anxious, uncertain and very worried about managing the communication of that diagnosis with their child, friends and family. For some, it can bring relief and a sense that they can now move forward as a family and locate the right pathways to support. Children can feel happy to know more about how their brain works and responds; that the way they understand and see the world has been understood and their needs responded to.

At the book launch, I spoke with many parents. One Dad had recently received a diagnosis of ASD for his daughter. I asked him about the first time he suspected that she needed an assessment. He told me that issues escalated emotionally when she started secondary school. Initially, she found the transition excruciating and was riddled with anxiety. Gradually, she began to manage by ‘bottling it all up’ at school and releasing her pent-up stress at the end of the day. As he put it, she seemed to be two different children all at once; the child who was well-behaved and ‘no trouble’ in school and the child he met at the school gate who, in his words, was an ‘emotional wreck, angry, tearful and incredibly tense’. Whilst he intuitively felt that she was bottling up all her emotional responses during the day and letting them flow out of her mind as soon as she saw him at the gate, he “didn’t understand that she was masking that whole time in school”.

So what is masking? Masking is when a neurodivergent person (someone with autism, ADHD or dyspraxia) uses strategies (consciously or unconsciously) to hide their differences and difficulties, and tries to fit in. Some of the following examples are taken from a great book called Autism and Masking: 1) when an autistic person makes eye contact when they don’t want to, 2) when an autistic person plans what to say before meeting someone, 3) when a person with ADHD comes up with phrases to use when they have zoned out and did not hear what a person has said, such as, “Oh, how interesting. How do you feel now overall?”, 4) when a child with dyspraxia pretends to forget PE gear to avoid the lesson, 5) when a neurodivergent person copies how other people talk and what they say, 6) when a neurodivergent person has a list of things to say to keep a conversation going. One strategy might be flipping the question back – “and what do you think?”

Sections of Dr Mooncey’s book had me thinking about gender differences in masking. Dr Mooncey suggests that girls’ masking may not be as easily detectable, as they seem to be more adept at coping behaviours than boys. She writes: “these girls may be model students but explode when they get home as they cannot continue the charade!”. She also notes that autistic girls are often very altruistic and empathetic (caring for younger children or engaging in prosocial acts), which can mean that ASD is not considered. Unfortunately, it is often falsely assumed that an empathetic disposition is incompatible with a diagnosis of autism.

Motivate

You might be reading this and thinking, but doesn’t everyone mask? To some extent, don’t we all mask how we really feel to get through daily interactions and manage everyday stress?

As PhD researcher, Ailbhe McKinney, explains, “The difference between masking as a neurodivergent person and a typical person is the amount of effort which goes into it. It is also more frequent.” You might also be thinking, but isn’t it just deceitful to pretend to be something you are not and to mask in social settings? Actually, we know from research that masking can often take place ‘unconsciously’, to avoid bullying, isolation or stigma. Masking is not about insincerity, but active coping. In their important article, Dr Amy Pearson and Kieran Rose call this “the illusion of choice”, explaining how, in many cases, ‘masking’ is a reaction to trauma.

I have described ‘masking’ as a coping mechanism, so you might be wondering why the Dad I met framed it as a ‘problem’. That is because he recognised that his daughter’s attempts to camouflage and mask her true self were cognitively exhausting. Masking can take a toll on wellbeing and on mental health; a recent review showed that, sadly, there is a link between masking and anxiety and depression. There are a few reasons for this.

Firstly, can you imagine pretending to be someone you are not all day? You are using more cognitive resources than other people all the time and then have nothing left for other tasks. Secondly, you may not be doing the things you actually want to be doing, or talking about the things you want to talk about. Pretending to be interested in something you’re not that into, or not being able to own up to your own music tastes and hobbies can feel debilitating. Finally, if you are masking all the time, you do not develop a sense of your own personal identity, because it can be hard to work that out. “Who am I really?”, can be a confusing question to answer.

So, should we try to stop children from masking completely? Hopefully, whilst reading this, you have reached the same conclusion as me. The first responsibility lies with the neurotypical population in developing empathy and understanding for those who see and interact with the world differently. Why should the neurodivergent change for the sake of others?

Support

Ultimately, we must work towards reducing stigma and creating a safe and accepting world for neurodivergent people, so that masking isn’t as necessary or as demanding.

So how can we move toward this new world? Schools should be safe environments which actively fight discrimination and stigma and have zero tolerance approaches to bullying. All parents can talk about difference, diversity and neurodiversity with their own children. Encouraging kindness and empathy towards people who don’t think, present or express themselves in exactly the same way as societal norms is hugely important, as is being open to learning about neurodiversity through literature and popular culture.

Parents of neurodiverse children can take excellent first steps to empower their own child regarding what they feel they have to do to get along with others, fit in and cope with the day. By reflecting and understanding more about their own masking behaviours, children learn that they do have agency and choice in certain situations. Knowing that you can unmask and thinking through when those moments might be, is empowering.

Tangible examples of parental support strategies can be found in a fantastic new book by Dr Hannah Belcher called Taking off the Mask. Beyond self-reflection, Hannah suggests that parents reassure children that there may still be instances where they feel like they have to act like everyone else, and that is ok. Masking can be tiring though, so developing self-advocacy strategies will be important as they grow up. Being able to articulate that they don’t want to do something, or need support to do so, is an incredibly important skill to hone over time.

Dr Belcher also gives some other important tips around building self-esteem and neutralising some of the effects of masking; 1) encourage your child to pursue their interests and passions, 2) give them neurodivergent role models, maybe in real life, but also famous people or through books written by neurodivergent people, 3) tell them they are loved unconditionally, and 4) help them prepare for events or changes that they might find difficult. Check out this free webinar from Dr Belcher to learn more.

Meanwhile, Dr Ailbhe McKinney, whose research we highlighted above, is conducting something called ‘The Transition to Teenager Project’ and is currently seeking girls to take part. The project aims to understand rates and experiences of masking, establish what leads to mental health problems and enable girls to voice what support they need. Adult women with autism, dyspraxia and ADHD contributed to the study’s design to ensure that it addresses high-priority research questions in line with the autistic, the ADHD and the dyspraxic community. The research team is seeking girls with a diagnosis of autism, ADHD, and/or dyspraxia (DCD), or those waiting to be assessed and are also interested in hearing from girls who do not have a neurodevelopmental condition. Their contribution could inform general understanding about the transition into adolescence.

If you do have a girl aged between 11 and 13.5, why not introduce the idea of research to her? Research participation (in this case two, 30-minute, online meetings over a year) can give children and young people a sense of agency in the world, help them to feel empowered around topics that others might consider taboo, and give them a sense of belonging to a wider community of like-minded young people. What’s not to like? Ailbhe is waiting for your email: a.m.mckinney@sms.ed.ac.uk or call/text 07388454435.

Are you a Tooled Up member?

We’re in the process of planning an online conference “All About Autism” to be held in April 2023 and want to hear from parents of autistic children or school staff interested in learning more about optimal ways to support pupils. Please get in touch and let us know your thoughts, comments and experiences.

We’re lucky enough to have already spoken with Dr Sophia Mooncey and her co-author, Adele Devine, about helping children with autism to thrive. Watch our webinar now and read the accompanying notes. If you want to learn more about neurodiversity, tune into our podcast interview with Dr Kathryn Bates or bust some neurodevelopmental neuromyths in this webinar with UCL scientist, Dr Jo Van Herwegen.

We also have interviews and presentations with experts on various different aspects of neurodiversity, including its potential impact on siblings, pathological demand avoidance, dyslexia, dyscalculia and tic disorders. Teaching staff might also be interested in our work on the link between nature-based learning and wellbeing in young people with autism and parents of older teens might like to take a look at our video and article on autistic young people’s experiences of transitioning to university, which were co-produced by a leading expert and a young person with lived experience.

Finally, it’s important to provide children with access to literature that features strong neurodivergent characters. This list will help.