February 11, 2026

Deepfakes and Damage

By Professor Elena Martellozzo and Emily Harman

Reflect

Artificial intelligence is transforming how images and videos are created, shared and manipulated, and it is doing so at a speed that few feel prepared for. What once felt like a distant, futuristic concern has become an everyday reality: AI-generated images are now part of children’s online lives, from playful filters to hyper-realistic deepfakes, produced in seconds. The tools that make this possible are no longer niche or technical. Many are free, widely advertised and available to anyone with a smartphone.

That widespread accessibility is precisely what makes this conversation so urgent. For parents, teachers and anyone working with young people, the rise of AI-generated non-consensual intimate images is not an abstract technological issue; it is a safeguarding challenge.

Yesterday was Safer Internet Day in the UK and this year, it focused on the safe and responsibly use of AI. We asked Professor Elena Martellozzo, a world leading expert in cybercrime, and Emily Harman, a trust and safety lawyer with a background in defending and prosecuting serious sexual offences, to share their expertise. Together, they explore the worrying rise of deepfakes (images, videos or audio clips created using AI to convincingly imitate real people), pulling back the curtain on these technologies to bring clarity to a fast-moving and often confusing landscape.

Our children are the first to grow up entirely online. Because they (and we) frequently share selfies and videos on social media, their images are widely available for "scraping" by AI tools. This makes them uniquely vulnerable to "nudify" apps that can transform children’s photos, often shared innocently on school websites or family social media, into explicit sexual content in seconds, without their knowledge.

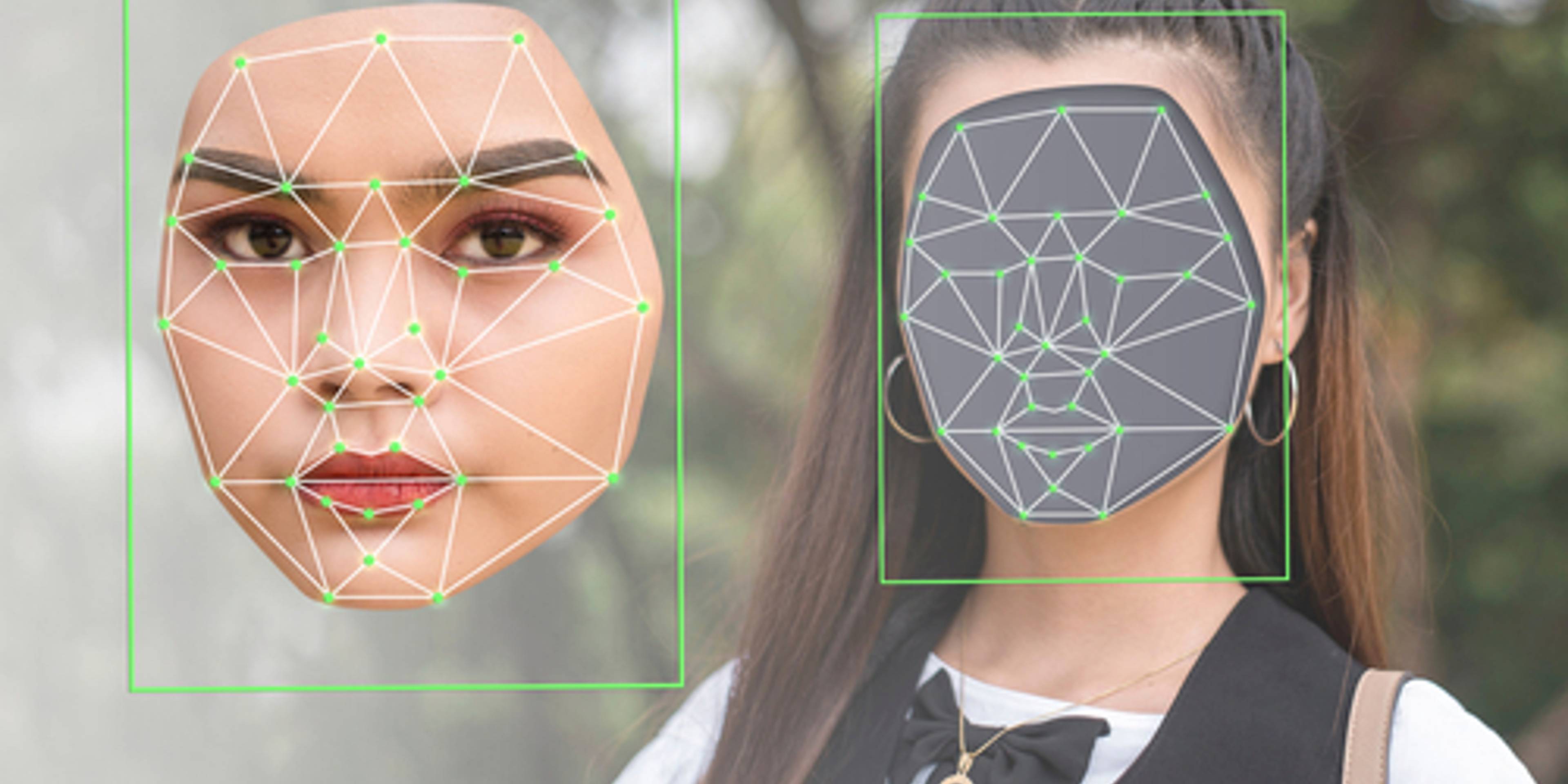

Think of traditional editing (like Photoshop) as a digital pair of scissors and glue; it requires manual skill to "cut" one face onto another. Generative AI is different. It acts like a digital artist that has studied millions of pictures to learn exactly how humans look, move and talk. When given a simple command, the AI doesn't just "paste" an image; it "generates" a brand-new, hyper-realistic version of a person doing or saying something that never actually happened.

While deepfakes can be used for harmless fun, making someone sing a silly song or adding special effects to a video, they are increasingly used as tools for harm, such as spreading misinformation or creating what’s known as non-consensual intimate imagery (NCII). In today’s digital world, we know well that we cannot believe everything we see. However, understanding that these images are “fake” does not lessen the very real harm they can cause a child or young person. The emotional, reputational and developmental consequences are profound, and the pace of change means adults are often left trying to catch up.

Technology moves much more quickly than legislation, and the law has been slow to keep pace. In the UK, it was only in 2023 that the sharing of intimate images without consent became a criminal offence regardless of motive (closing the long-criticised “intent to cause distress” loophole). But even that reform left a gap. The law still focused on real images. It was not until mid-2025 that Parliament addressed synthetic, AI generated or manipulated content. Today, the UK’s rules on NCII sit across three separate Acts: Sexual Offences Act 2003, the Online Safety Act 2023 and the Data (Use and Access) Act 2025. Taken together, they finally recognise that intimate image abuse now includes both genuine and AI-generated content. Globally, the picture is even more fragmented. Only a small number of countries have enacted laws that explicitly address synthetic NCII. Many still lack even basic protections against intimate image abuse, whether genuine or AI-created.

Motivate

Recently, nudification apps have received much political and social scrutiny, with the UK Government describing the use of declothing-focussed AI as “devastating to young people’s lives”, and as a technology “weaponised to abuse, humiliate and exploit victims”. But the abuse which sees safe-for-work pictures, family photos and professional headshots transformed into sexualised imagery is all too commonly perpetrated using publicly available tools. We tested an app and here is our experience.

Mainstream AI providers often have community guidelines for safe and lawful use of the tools. And they have, for the most part, trained their AI to refuse explicit requests to create illegal content. But regrettably, it does not take much creativity to circumnavigate many of these guardrails. We deepfaked ourselves in under five minutes on one mainstream tool. We will not name it, but suffice it to say everyone’s heard of this one.

The AI told us it could not ‘sexualise an image’ or ‘alter your body’, and refused a request to reduce clothing coverage. And yet, with a few prompts, we created a version of ourselves with augmented breasts which were mostly on display save for a tiny bit of PVC covering. By way of reminder, the definition of an intimate image in the newly updated Sexual Offences Act includes content which shows “all or part of the person’s exposed genitals, buttocks or breasts”. And the Data Use and Access Bill amendments include “all or parts of a person’s exposed breasts” in the scope of purported sexual images.

Another easily accessible mainstream tool asked us what changes we wanted, after we challenged if it could edit images. It gave us a list of examples which included ‘face swap’. After we changed the outfit we were wearing to feature PVC shorts and a crop top, it also (unprompted) asked us if we wanted to add ‘latex fetish style’. When we clicked this, it then asked if we wanted to add such styles as ‘dominatrix’, ‘add a riding crop or whip’, or most concerningly ’add torn lace knickers’. Without much friction at all, we were able to generate a highly sexualised video. Had this image been of someone else, we would have been guilty of committing a criminal offence, and the AI tool in question would have encouraged our commission of this. That’s how simple it is.

AI-generated non-consensual intimate images pose a rapidly escalating threat to children’s rights, safety and wellbeing. From a children’s rights perspective, this is not just a "digital prank". It is a violation of the fundamental protections promised to every child under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). This includes their right to privacy, their dignity, their identity and, most crucially, their right to be free from exploitation.

Deepfake sexualisation is exploitation in its purest form. It is a common misconception that if an image is "fake" or "synthetic", the damage is somehow less significant. The reality is that while the image is generated by a machine, the harm to the child is real, lasting and damaging. This technology creates new forms of child sexual abuse material, as confirmed by the Internet Watch Foundation. Children no longer need to be physically present for an abuser to create explicit content; a single photo scraped from a school website or a social media post can be weaponised against them. This represents a total loss of control over one’s digital identity and a profound violation of bodily autonomy.

Unlike physical bullying, AI-generated abuse also suffers from the "persistence problem". Once a deepfake is created, it can be copied, shared and stored indefinitely across the dark web and encrypted apps. For a child, the discovery of such an image, or even the mere threat of its existence, can lead to devastating developmental and psychological harm. It fuels harassment, reputational damage and "sextortion", where fake images are used to coerce children into real-world sexual acts or financial payments. And because children cannot meaningfully consent to the manipulation of their likeness, these acts are inherently predatory.

Beyond individual harm, this trend erodes societal trust. As deepfakes become indistinguishable from reality: real victims may be disbelieved when they claim a genuine video is "just an AI fake", while perpetrators use the same excuse to evade justice. For children, this creates an environment of digital insecurity where their online presence feels like a liability rather than a space for expression.

Support

Equipping our children to recognise manipulated media is a cornerstone of modern digital literacy and a vital safeguarding tool. Schools can lead this effort by integrating AI literacy into PSHE, computing, or media studies, ensuring students understand the mechanics of synthetic media.

Young people are often unaware of the seriousness of creating a deepfake. They often underestimate the psychological effect on a victim of image abuse, and minimise instances where “it’s not really them”. Given that the UK, a fairly progressive legislating nation, has only just criminalised a creation offence, school pupils can be forgiven for not fully comprehending the seriousness. Education around this is key, to ensure that children appreciate the consequences and criminality of deepfake creation, and to ensure that they appreciate this impact before they fall victim themselves to scenarios like synthetic nudes being created and shared around their year group. Advice for parents and educators can be found through organisations including SWGfL, Childnet, the Internet Watch Foundation and via this free toolkit from University College Cork.

It is vital for parents and teachers to understand that children who create or share AI-generated intimate images, even as a "joke", may be inadvertently committing a serious criminal offence. In many jurisdictions, including the UK and several EU Member States, these actions are treated as the production and distribution of child sexual abuse material. The legal framework is clear: an image does not have to be real to be illegal. If it depicts a minor in a sexualised way, it falls under strict criminal definitions. Even having such an image on a phone or device can be a criminal offence. Staying informed about the law gives us the tools to help young people protect their digital footprints and move through this new digital landscape with greater safety and confidence.

Schools have a large role to play. In recent conversations we have had with young people, many told us that they would actually prefer to learn about these topics in school, largely because they feel uncomfortable discussing them with their parents. Last year, we saw a significant push from the Government, encouraging schools to address misogyny directly, including teaching about pornography and the forms of technology-facilitated violence that disproportionately affect women and girls. From September 2026, schools in England will also be required to educate pupils about deepfakes, including how they can be used maliciously as well as for entertainment, the harms they can cause, and how to identify them. The PSHE Association has produced some free lesson plans for Key Stages 2 - 4, which you can access here.

Programmes like the Schools Consent Project speak to pupils about consent, the law surrounding sexual violence and the legal framework around creation of synthetic news. The volunteers are always surprised about the level to which NCII is minimised, when it is AI-generated. The fact remains that we need tomorrow’s society, our children today, to evolve faster than the law has and understand how harmful the use of AI to create sexualised media can be.

So how do we talk to our children about deepfakes at home? The answer is actually not complex. Creating a shame-free home culture is key, as is encouraging them to ask questions without embarrassment. We should also try to strike the balance between reassuring children that curiosity about sex, porn and AI is natural, but that not everyone seeks these things out and that’s ok too. One risk of open conversations about subjects such as porn and AI-generated sexualised imagery is that we may inadvertently encourage it, or suggest that using AI tools to create deepfakes is so widespread and normal that our children feel peer pressure or a curiosity to start doing it.

The basis of much RSE education is consent, respect and boundaries. Education around deepfakes and digital privacy is the same, and a good starting point for parents of younger children is to focus on asking for permission in innocuous settings, as well as demonstrating healthy boundaries around digital consent and modelling healthy digital habits. It may sound extreme, but if we post pictures online of our children in swimwear without asking their permission, what example does that set for kids growing up about asking permission from a peer before adding that scantily clad photo to their socials.

Using AI tools to create harmless yet digitally altered hyper-realistic depictions should also be monitored. And it should start with the digital alterations that are not unlawful but still harmful, before AI tool use escalates. An example of this could be someone changing the outfit on a classmate to dress them in something ‘uncool’ and designed to humiliate.

We can also promote critical thinking through interactive play, using educational games and "real vs. AI" quizzes to test children’s ability to discern fact from fiction. By teaching children to question the authenticity of what they see, we do more than just protect them from the harms of digitally altered sexualised media; we build their resilience against wider misinformation and online manipulation with care, confidence and compassion.

Are you a Tooled Up member?

If you want to learn more about this topic, you might like to look at AI Chatbots and Deepfakes - New Developments Parents Need to Know About

Keep your eyes peeled for our brand new webinar with Laura Knight on the safe and responsible use of AI, which will be added to the platform soon.

We're hiring!

Our busy research team is looking for a new Research Assistant to help us translate high-quality evidence into practical guidance for parents and educators. If you’re interested, or know someone who might be, we’d love to hear from you.